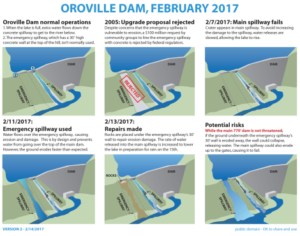

Last week California’s Oroville Dam, the tallest dam in the United States, almost failed due to a surplus of water filling Lake Oroville. As the lake filled higher and higher, water was being released, via spillways, into the Feather River. The volume of water caused erosion of the dam’s main spillway, causing it to crater and break apart. As a result, the dam’s emergency spillway began to erode. That spillway had never been used and was unlined. The lack of concrete lining may have led to its erosion as well.

Nearly 200,000 people were evacuated from the area, many of them fleeing to higher ground cities like Sutter. As the water began to recede, residents began to travel back home.

But what went wrong? What caused the damage in the first place?

The Oroville Dam project was approved in by voters in 1960, when there were just 16 million people living in California. Now there are 40 million residents living in the state, and its waterworks were not designed to service so many people or deal with severe weather. They are inefficient and aging. They also weren’t designed to cope with the climate change we’re experiencing today. It’s important to note that California has always experienced wet and dry periods. However, the problem is the severity of the weather – which is attributed to climate change.

The American Society of Civil Engineers gave Oroville and many other United States dams a “D” grade because the dams are aging and underfunded. According to John France, an expert with the ACSE, “Designers of older dams didn’t know as much as engineers do now about how dams perform when stressed, which can lead to design deficiencies.”

For several years, environmentalists had warned that the emergency spillway should be lined with concrete. Government officials ignored the warning, as the project would cost a lot of money and nobody wanted to allocate the money or foot the bill.

Now forensic engineers are looking at the dam to try to understand what caused the damage. Did the soil beneath the spillways dry out due to the drought?

“Was something wrong with the concrete? Did something happen underneath? Lester Snow, former state water director, wants to know. “If we can’t rely on the main spillway, we can’t ever fill Oroville again.”

One possible theory is cavitation, which happens when fast-moving water creates explosive vapor-pockets that cause concrete to shatter.

Forensic engineers will have a tough time investigating. Unfortunately, much or all of the evidence has washed away. There will be no real way to accurately pinpoint whether the disaster was the result of bad maintenance or bad design. Not only that, the main priority of officials is to get the dam functioning safely again, not on what lead to the disaster. That investigation will come later.

As a second round of severe storms (but not as severe as the first) ran through the state, officials worked to slow the drainage of the lake and allow work crews and engineers to begin clearing soil, rocks and debris from the damaged spillways and the Feather River. The debris had impacted the downstream hydroelectric plant, causing it to cease operations. Efforts to reinforce the emergency spillway before more rain arrived included the use of helicopters and trucks to fill three deep craters in the dirt hillside with cement and large rocks.

According to state Department of Water Resources acting director Bill Croyle, just prior to the second storm, repairs on one erosion site were done. Repairs to the second site were at 25%, and repairs to the third site were at 69%, Croyle said.

According to early estimates, repairs to the dam could run $200 million dollars or more.